Pictures from Old Germantown: the Pastorius family residences are shown on the upper left (c. 1683) and upper right (c. 1715), the center structure is the house and printing business of the Caurs family (ca. 1735), and the bottom structure is the market place (c. 1820).

Pictures from Old Germantown: the Pastorius family residences are shown on the upper left (c. 1683) and upper right (c. 1715), the center structure is the house and printing business of the Caurs family (ca. 1735), and the bottom structure is the market place (c. 1820). A Map of the County of Philadelphia from Actual Survey / 1843, Charles Ellet Jr.

A Map of the County of Philadelphia from Actual Survey / 1843, Charles Ellet Jr.The thirteen families who settled Germantown were Mennonites and Quakers, and Germantown is also notably the birthplace of the anti-slavery movement in America. Abraham op den Graeff came from Krefeld, Germany, noted for its role as the center of the German textile industry, and a city of weavers. He founded an early Germantown linen industry, modeled after that of Krefeld, and soon won the first Governor’s Award from William Penn for producing the finest linen woven in the colony. This established Germantown as the early center for textile manufacturing in Pennsylvania, and it would grow into its reputation as a place for reliably good quality material and goods throughout the colonial and early republic periods. While Germantown was known for its linen industry in the early days of the colonies, it was their production of woolen yarns that would catapult them into the national spotlight in years to come.

Germantown textile manufacturing was developed as a cottage industry, and it would remain so up until the beginning of the Civil War. At this time, industrialization spread, and other neighborhoods in Philadelphia like Kensington and Manayunk started to produce larger quantities of goods, but Germantown saw a smaller expansion with producers continuing to work out of their homes. Industry in Germantown gradually moved from cottage style manufacturing to smaller mills, but Germantown maintained significantly higher wages than its heavily industrialized counterparts and was able to resist the labor strife inherent to industrialization into the end of the 19th century. It was in this period that producers like Joseph Fling’s Germantown Yarn Mill (below) and J. Randall’s Franklin Yarn Mill grew. Buoyed by Civil War contracts for woolen military uniforms and hosiery and post-war protectionist tariffs, the woolens industry in Philadelphia was in a good position. In addition, the federal government would soon start buying quantities of Germantown yarns in order to supply the newly created reservations in the Southwestern United States with weaving yarns. The Navajo in particular are reported to have lost up to two-thirds of their sheep during the cruel forced relocation imposed upon them by the US government, and supplying them with yarn was used as a means of softening the harsh blow that the communities felt. This move has a dark side. The relocation of Native Americans and the import of these commercially produced wool both hastened disease among both people and the sheep they tended. Some beautiful weavings were produced in this period, but that is far diminished by the reality of the full story. If you would like to know more, the book Rainbow Yarn : Navajo Weavings, Germantown Yarns & the Pennsylvania Connection is highly recommended, if you can find it. Aboriginal life among the Navajoe Indians. Near old Fort Defiance, N.M. / Library of Congress / 1873, T. H. O'Sullivan.

Aboriginal life among the Navajoe Indians. Near old Fort Defiance, N.M. / Library of Congress / 1873, T. H. O'Sullivan. Navajo Germantown Eye Dazzler Rug: Rectangular woven rug; red, grey, and black integrated diamond design on a natural colored field with black border; small black knotted tassel on each corner. / Science History Institute. / 2008, Gregory Tobias.

Navajo Germantown Eye Dazzler Rug: Rectangular woven rug; red, grey, and black integrated diamond design on a natural colored field with black border; small black knotted tassel on each corner. / Science History Institute. / 2008, Gregory Tobias. Wm. H. Horstmann & Sons, Phila., Pa, Exhibit of Germantown Yarns in the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia. #711, Main Exhibition Building, Bldg. #1. / Free Library of Philadelphia / 1876, Centennial Photographic Co.

Wm. H. Horstmann & Sons, Phila., Pa, Exhibit of Germantown Yarns in the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia. #711, Main Exhibition Building, Bldg. #1. / Free Library of Philadelphia / 1876, Centennial Photographic Co.

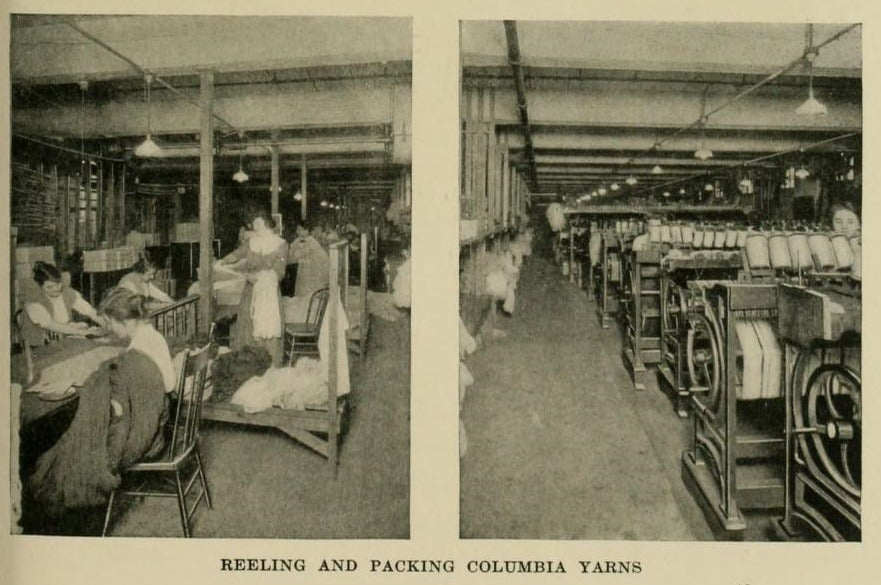

Reeling and Packing Columbia Yarns. One hundred years, 1816-1916; the chronicles of an old business house in the city of Philadelphia / 1916, Wm. H. Horstmann Co.

Reeling and Packing Columbia Yarns. One hundred years, 1816-1916; the chronicles of an old business house in the city of Philadelphia / 1916, Wm. H. Horstmann Co.

Fleisher Yarns ad from 1919 / Collection of Kelbourne Woolens.

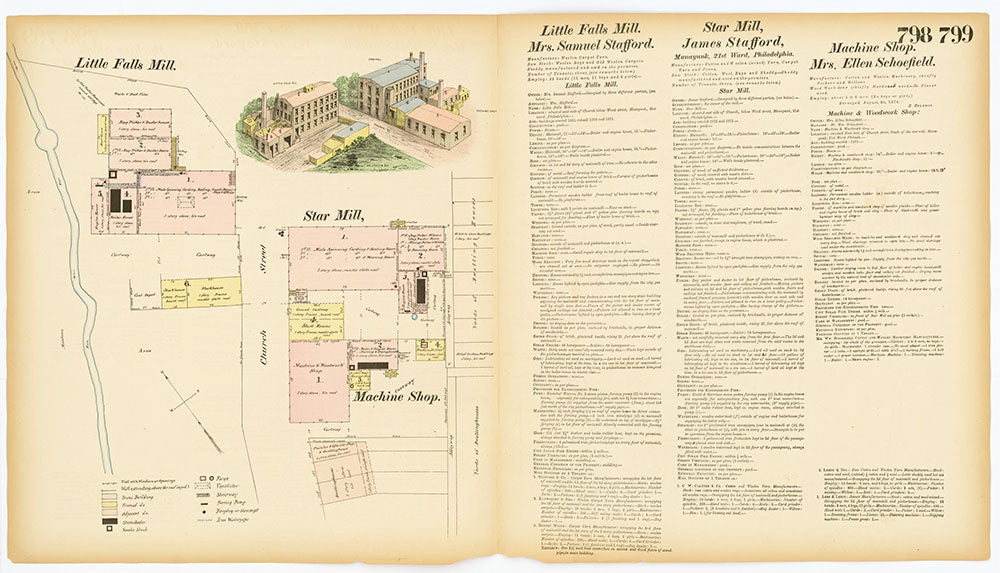

Fleisher Yarns ad from 1919 / Collection of Kelbourne Woolens. Hexamer General Surveys, Volume 9, Plates 798-799 / Free Library of Philadelphia / 1874, Ernest Hexamer.

Hexamer General Surveys, Volume 9, Plates 798-799 / Free Library of Philadelphia / 1874, Ernest Hexamer.Thanks, Nic!